Brief Synopsis

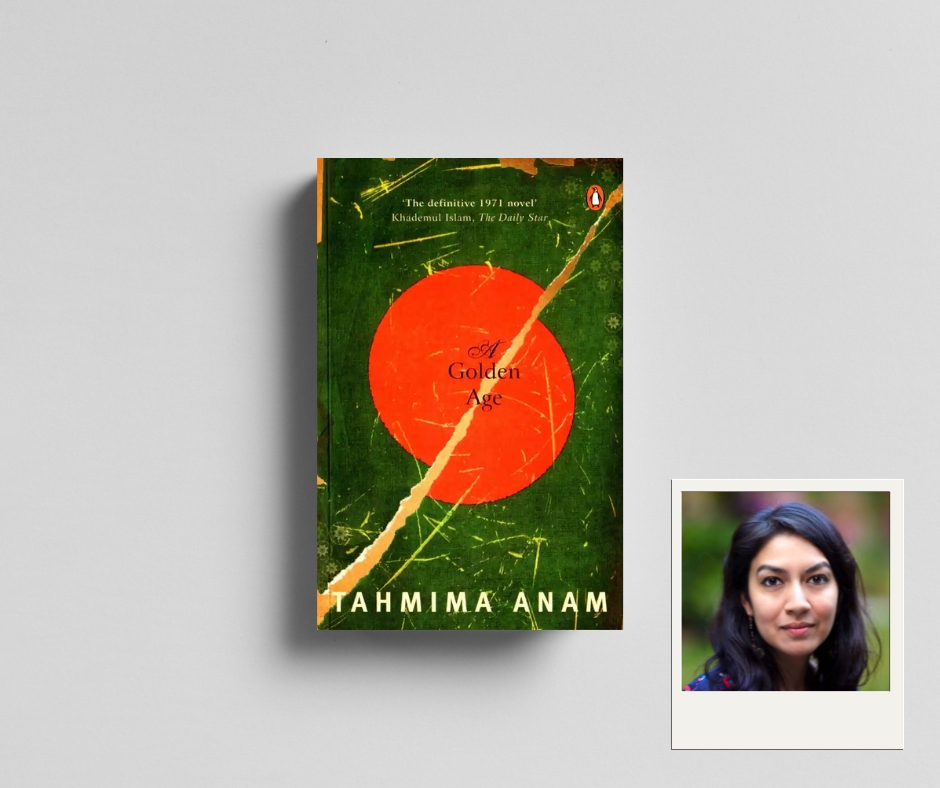

Tahmima Anam’s A Golden Age tells the story of Rehana Haque, a widowed mother struggling to protect her children during Bangladesh’s 1971 Liberation War. While the novel vividly depicts the violence of Pakistan’s military campaign – which killed millions and displaced countless others – it also celebrates Bengali culture through rich depictions of food, poetry, and resilience. Rehana, an Urdu-speaking woman from West Pakistan who has made East Pakistan (later Bangladesh) her home, embodies the nation’s fractured identity. After losing her children in a custody battle years earlier, she is determined not to fail them again when war erupts. Though initially reluctant, she becomes increasingly involved in the resistance, sheltering rebels and aiding the cause, even as her son and daughter join the fight. The novel explores themes of sacrifice, guilt, and national identity, blending personal and political struggles against the backdrop of a brutal conflict. Anam’s debut, the first in a planned trilogy, is both a gripping historical narrative and a poignant tribute to Bangladesh’s birth.

SUMMARY

The Prologue begins with Rehana Haque’s inner voice addressing her deceased husband, declaring that she has lost their children. The narrative then shifts to a recent day when Rehana visits the courthouse. After leaving the court, where she has lost custody of her children, she purchases two kites – a red one and a blue one – from Khan Brothers Variety Store and Confectioners. The shopkeeper wraps the kites in brown paper and ties them with jute ribbon. Rehana tucks the kites under her arm and boards a rickshaw.

As she gets in, her lawyer runs after her to apologize, advising her to find some money if she wants to regain custody. He explains that bribes might help influence the court. Rehana does not respond and quietly instructs the rickshaw driver to take her to Dhanmondi, Road Number 5.

At home, she finds her children, Maya and Sohail, sitting on the sofa. Maya cheerfully calls out to her, while Sohail looks down at his palms. Rehana, having already cried during the rickshaw ride, struggles to contain her grief in front of them. She gives the children the kites. Maya tears into hers excitedly, but Sohail only strokes his quietly.

Rehana informs them that they are going to live in Lahore with their uncle Faiz Chacha. Maya reacts with surprise. Rehana apologizes to Sohail and tries to comfort them by speaking about flying the kites in Lahore, suggesting they will fly them back to her one day. She encourages them to be brave and promises they will return soon.

Later, Rehana takes the children to the Azimpur graveyard to say goodbye to their father, Iqbal. The graveyard is filled with other mourners. Rehana holds her children’s hands and guides them to Iqbal’s grave. Sohail recites a prayer. Rehana tells Maya to say goodbye, and Maya does so, distracted by a butterfly.

Flashbacks reveal that the judge deemed Rehana unfit to raise her children due to her youth and emotional state after Iqbal’s death. The judge believed she had not taught them properly about religion and the afterlife. Faiz, Iqbal’s elder brother, argued that the political instability in Dhaka made it unsafe for the children and that Lahore, where he lived with his wealthy, childless wife Parveen, was a safer environment.

Faiz, who never liked Rehana due to Iqbal’s devotion to her, told the court anecdotes to portray her as an unfit mother. He mentioned that Rehana once took the children to see Cleopatra, questioning the film’s suitability. He also recounted the story of Iqbal’s marriage decision being based on a coin toss, portraying Rehana as the result of chance rather than choice.

Rehana reflects on her marriage, her widowhood, and the lack of family support nearby. Faiz and Parveen offered to take the children temporarily, claiming it would give her time to recover. When she refused, they filed a legal case. In court, Faiz argued that Rehana needed rest and that the children’s welfare was the priority.

Rehana recalls Iqbal’s sudden death – how he collapsed in front of the house one January day, clutching his pocket watch as if to record his final moment, and whispering “Forgive me.” She reflects on her isolation and poverty following his death. During the hearing, she could not affirm with certainty that she could care for the children, which led the judge to award custody to Faiz.

After the verdict, Rehana watched the children leave on Pakistan International Airlines Flight 010 to Lahore, carrying their kites. She stood at the airport, watching through a window fogged with hair oil and fingerprints. Parveen called later to confirm they had arrived safely, but Rehana could barely hear her through the crackling line.

In the following days, various acquaintances and relatives visited Rehana, offering sympathy. She regarded them as “grief tourists.” Only Mrs. Chowdhury brought her daughter Silvi to visit. Mrs. Chowdhury scolded Silvi for sulking and encouraged Rehana to remain hopeful. Rehana invited Silvi to stay for a meal, although she had little food at home. Silvi asked to see Roman Holiday as promised, but Rehana only replied, “Next time.”

Rehana began writing letters to her children. Her early drafts were emotional, but she discarded them, fearing they might confuse or upset the children. Instead, she wrote cheerful, factual letters, maintaining the illusion of normalcy. She noted things like Maya’s favorite color being blue, and Sohail’s being red. She described Sohail’s scar and recounted a humorous memory involving it.

She tried to recall and preserve memories of her children’s personalities and quirks – who was quiet, who was playful, who liked certain foods, and who loved certain actors. She remembered Iqbal’s deep concern for their safety and health.

The narrative then shifts to a flashback of Maya’s fourth birthday. Iqbal had recently acquired a new Vauxhall car and was excited about it. For Maya’s birthday, the family planned a short train ride from Tejgaon to Phulbaria. Rehana prepared food, Maya wore a blue satin dress with ribbons and lipstick, and Iqbal fussed over the travel arrangements. Sohail wanted to sit in the front seat, but Iqbal insisted he stay in the back for safety. They all squeezed into the back of the car, with Maya’s puffy dress taking up much space. Rehana observed all of this, noting Iqbal’s concern and his care for the family.

The Prologue ends with Rehana still overwhelmed by memories, trying to write to her children, and struggling with the loneliness and loss that have come to define her life.

On the first day of March, Rehana prepared for her annual celebration at Road 5, which she held every year to commemorate the day she had returned to Dhaka with her children. She saved her meat rations and prepared biryani, arranged for hired chairs, and called the jilapiwallah to fry sweets in the garden. She also arranged a red-and-yellow tent for rain and prepared lemonade, cucumber salad, and spicy yoghurt. The guest list remained consistent each year: Mrs Chowdhury and her daughter Silvi, her tenants the Senguptas and their son Mithun, and Mrs Rahman and Mrs Akram, known collectively as the gin-rummy ladies.

Before dawn, Rehana stepped into her garden. The air still held the cold of winter, and a light fog hovered over the lawn. She walked among her plants, plucking a dew-covered rose and moving past jasmine, hibiscus, and fruit trees. As she moved, she looked at her larger, newer house, Shona, built to save her children. Though faded by age and weather, the house still stood tall behind the bungalow, both houses built with their backs to the sun. Rehana reflected on how the house symbolized both her triumph and her loss. She had named it Shona (gold) for everything it had cost and everything it represented.

Rehana returned indoors, touched the furniture fondly, and prayed. This was part of her daily ritual: to awaken before sunrise, move through her home, pray, and then wake her children. Although Maya and Sohail were now nineteen and seventeen, she still thought of them as her children. She woke Maya gently, reminding her it was their anniversary. She gave Sohail the rose she had plucked.

While her children bathed, Rehana ironed their new clothes. She wore an egg-blue sari; Maya had a blue georgette with yellow polka dots, and Sohail wore a brown kurta-pyjama with a collar embroidered by Rehana. Maya expressed reluctance about her outfit, citing her activist commitments, but she wore it regardless. After dressing, both children touched Rehana’s feet for blessings. She hugged them, observing how much they had grown. Sohail resembled her in appearance, while Maya bore her late father’s features and seriousness.

They left for the cemetery in rickshaws, Rehana following behind her children, watching them fondly. Along the way, Rehana thought about her estranged sister Marzia, who had visited from Karachi but disapproved of Rehana’s choices. Despite Marzia’s judgment and comments on Rehana’s language and life in Dhaka, Rehana continued to think of her family in the western part of the country, although she never sent the letters she wrote to them.

Upon reaching the graveyard, Rehana gave a few coins to the caretaker and passed graves of acquaintances. She reflected on an old man who visited his wife’s grave daily and considered herself the second-most devoted mourner. Rehana maintained her husband Iqbal’s grave with care, having planted jasmine flowers around it. She now stood at the foot of his grave with her children.

She began her silent prayer to Iqbal, updating him on the children’s ages and the current political situation, particularly the uncertainty following recent elections and the delay in declaring Mujib as Prime Minister. She ended the prayer with a simple goodbye. When she opened her eyes, she noticed Sohail brushing away tears and Maya touching and kissing the headstone.

They returned to prepare for the day’s celebration. Maya cleaned the drawing room, and Sohail assisted with the garden decorations. Rehana uncovered the biryani she had cooked overnight and mixed the layers of rice, meat, and potatoes evenly. She counted plates for the approximately twenty guests and grew nervous, as she did each year. Since Iqbal’s death, she had stopped attending the Gymkhana Club and rarely saw her friends outside this event.

Rehana recalled how her friends once tried to encourage her to rejoin the club. Mrs Rahman brought cake, Mrs Chowdhury came with Silvi, and Mrs Akram often acted uncomfortable. Though they initially respected her grief, they expected her to return to normal after the children’s return. Rehana once tried to rejoin them at the club but found herself alienated.

She remembered one particular game of gin rummy. The card table had flower-patterned tiles labeled with flower names. The other women were cheerful and lively. Mrs Chowdhury had hinted at a surprise, but Rehana felt uneasy and hot in the unfamiliar atmosphere. Despite her effort to participate, she could not reconnect with the group as she once had.

A waiter entered the room with a tray of teacups and biscuits. Mrs Chowdhury dismissed him and took charge of the tea service herself. She poured whisky from a silver flask into the cups, followed by real tea and milk, announcing the drinks were ready. When Mrs Akram questioned what was in the cup, Mrs Rahman identified it as whisky and urged everyone to drink, claiming they deserved it.

Mrs Rahman attempted to catch Rehana’s eye. Though there was initial hesitation, Mrs Chowdhury lifted a cup and joked that Rehana needed some mischief since she was not getting married. This comment led to nervous giggles from Mrs Akram. Rehana, influenced by the sugary aroma of the whisky, agreed to try it. She recalled a brief, intimate moment when Iqbal had offered her a taste of whisky in the past. She now took a tentative sip, prompting the others to join in. Mrs Chowdhury clapped in delight.

The women began playing cards. Rehana won the first round, Mrs Rahman the second, and during the third round, Mrs Chowdhury incorrectly declared victory but justified it by saying that bringing the whisky should earn her some credit. The mood turned more pointed when Mrs Akram asked why Rehana refused to marry. Surprisingly, Mrs Chowdhury joined in, expressing concern.

As all three women stared at her expectantly, Rehana felt the whisky settle uneasily in her stomach. She was no longer able to mask her true feelings with humor. Internally, she acknowledged that she had no desire to remarry. She had considered it once before building Shona, but after her children returned, the need for romantic love vanished. She feared the potential harm a man might bring to her children.

She did not voice any of these thoughts to the others. Instead, she gradually stopped attending the card games. She initially claimed a headache, then used her children’s illnesses as reasons to stay away. Eventually, the invitations stopped, and Mrs Sengupta replaced her. Rehana suspected the others gossiped about her aloofness and refusal to marry, but she accepted their misunderstanding as inevitable.

One day, Mrs Chowdhury arrived first for a gathering at Rehana’s house. Hearing her at the gate, Rehana asked Maya to watch the biryani and went to greet her. Mrs Chowdhury entered cheerfully, carrying a box of laddoos and proclaiming she had news. She was followed by a tall man in military uniform and her daughter, Silvi, dressed in ornate jewellery. She introduced the man as her son-in-law, feeding Rehana a laddoo and explaining that they were not yet formally engaged.

The uniformed man greeted Rehana formally, and she responded politely. Mrs Chowdhury praised his appearance and quiet nature, believing he was well-suited to her shy daughter Silvi. She proudly added that he was a lieutenant, seeing this as a prestigious match.

As Rehana contemplated how to break the news to Sohail, the Sengupta family arrived, knocking on the drawing-room window. Rehana welcomed them in. Mrs Sengupta appeared stylish and imposing, while her husband seemed small and nervous. Their son, Mithun, requested tea due to a headache, but Rehana and his mother insisted on an orange cola instead.

Meanwhile, Sohail and Maya were preparing food in the kitchen. Rehana, anxious to avoid a confrontation between Sohail and Silvi’s fiancé, sent Sohail on an errand to buy more sweets. Although he was irritated, she gave him money and instructed him to take a rickshaw and exit through the back to avoid being delayed by guests. He complied, and Rehana watched him leave with guilt.

Maya quickly noticed something was wrong. When she questioned Rehana, her mother revealed that Silvi was getting married. Maya was shocked and frustrated by how quickly the match had been made. She jabbed her cucumber slices and asked what they should do. Rehana replied that the most important thing was to prevent Sohail from encountering the couple when he returned.

Back in the drawing room, Mrs Rahman and Mrs Akram arrived. The pair always travelled together and appeared eager to escape domestic life. Rehana felt relieved by the growing number of guests, as it helped shift attention away from Silvi and her fiancé. She brought out the biryani and announced that lunch was ready. The guests gathered around the table as Rehana served the food and distributed plates.

Mrs Akram comments on the festive atmosphere, referencing a wedding. Rehana is actively hosting, serving biryani and offering vegetarian dishes to accommodate the dietary needs of her guests, including Mr Sengupta. She dismisses his concern about hospitality by reminding him that it has been ten years since he and his wife moved in, implying they are more like family than tenants.

In a quieter moment, Rehana finds Silvi in the corridor. Silvi compliments the biryani, calling it the best in Dhaka. Rehana, still preoccupied with unspoken concerns, tries to maintain a friendly tone. She gently addresses Silvi’s upcoming marriage. Silvi admits that her mother’s health—specifically her high blood pressure—was a major reason for her decision. Rehana remarks that Silvi’s mother appears pleased and comforts Silvi with a tender gesture.

Later, Sohail enters the scene with sweets, but Rehana is too burdened with dishes to stop him before Mrs Chowdhury intercepts him. She eagerly informs Sohail of Silvi’s engagement and introduces him to her fiancé, Lieutenant Sabeer Mustafa. Sohail’s reaction is subdued but polite, welcoming Sabeer to the family. Rehana attempts to divert Sohail to help with the dishes, but he deflects by offering cricket match tickets, inviting the guests, including Lieutenant Sabeer and Silvi. Silvi’s mother declines on her behalf, citing wedding preparations. Maya pointedly accepts, hinting at tension between her and Silvi.

As guests relax under the tent, Mr Sengupta changes the topic to politics, asking Sohail about the student movement. Sohail explains the growing unrest: although Sheikh Mujib won the election, the assembly has not yet convened, and the students are becoming frustrated. Mr Sengupta expresses hope for diplomacy, but Sohail counters that the West Pakistani leadership is stalling and bleeding East Pakistan dry. Sohail grows impassioned, criticizing the lack of resources and autonomy in East Pakistan. Sabeer questions the feasibility of independence. Sohail responds angrily, citing economic and cultural exploitation. Mr Sengupta tries to moderate the discussion by attributing hardships to natural disasters like the cyclone, but Sohail insists starvation is caused by governmental negligence. Exhausted, he ends with the belief that independence is now necessary.

Sensing the tension, Rehana quickly distributes bottles of orange cola to lighten the mood. The guests respond politely, sipping their drinks, and the atmosphere gradually calms.

As the event winds down, Rehana and her friends move to the kitchen to clean up. She complains about the leftover biryani and jokes about sending it to the mosque. Mrs Chowdhury requests a portion, already calculating its value for future meals. The women begin discussing Sohail’s political involvement. Rehana tries to downplay it, saying he has tried to stay out of politics, but the others insist he seems quite engaged. They compare Sohail to their own children, who appear more conventional and obedient.

The conversation takes a sudden turn when Mrs Chowdhury jokes that Sohail should spend his energy chasing girls instead of politics. This awkward comment leads to a charged silence. Rehana becomes aware that something deeper is about to surface. Mrs Rahman breaks the tension by revealing that Sohail is in love with Silvi. There is laughter, denial, and awkward attempts to dismiss the notion as childish or outdated. Rehana remains silent, absorbed in washing dishes, unwilling or unable to respond.

Maya interrupts the tense kitchen scene, announcing that Sohail is sitting in the garden with his head in his hands. Rehana quickly tells her to bring him lemonade and hands her a glass. Maya senses the strange atmosphere in the kitchen but leaves without asking questions.

As Maya leaves, the conversation continues. Mrs Chowdhury insists she did not know about the affection between their children and seeks Rehana’s agreement that a relationship between Silvi and Sohail would be a bad idea. Rehana, despite her pain, agrees to avoid further embarrassment for her son.

Mrs Rahman laments the situation, calling it a shame, but Rehana cuts her off, clearly distressed. She urges the women to leave, stating that her children will help with the cleaning. They say goodnight softly, sensing her discomfort. Rehana whispers a farewell, unsure if they heard her. The kitchen becomes a space heavy with tension, regret, and quiet sorrow, filled with the fading scent of biryani and the hum of overhead light.

Later in the evening, after the children had fallen asleep, Rehana lay down beneath her mosquito net. She pulled the katha up to her chin and began to reflect on the evening’s events, particularly the episode with Silvi. She wondered if there was something she could have done to prevent it. Sohail had avoided her all evening and had gone to bed without drinking his tea. When he said goodnight, Rehana thought that the way his mouth was set carried a silent accusation.

Rehana recalled Mrs Chowdhury’s critical comment about Sohail: “He’ll never make a good husband. Too much politics.” The remark had hurt Rehana, perhaps because it carried a degree of truth. Recently, both of her children had been consumed by political involvement. This change had begun when Sohail joined the university.

Rehana then reflected on the broader political history of East Pakistan. Since 1948, the Pakistani authorities had governed the eastern region like a colony. They had attempted to impose Urdu over Bengali, diverted jute revenues from Bengal to develop cities like Karachi and Islamabad, and failed to honor political promises. In response, students from Dhaka University had led protests, and it was no surprise that both Sohail and Maya had become engaged in political activism. Rehana herself could understand their frustrations, especially the illogical geography of a country split in two across India.

A major turning point had occurred in 1970 when a devastating cyclone struck. Rehana remembered the day when Sohail and Maya returned from a rescue operation. Their eyes were bloodshot as they described the rising waters, the floating bodies, and their desperate wait for food trucks that never arrived. The government had never sent the aid. This event clarified the injustice and led Maya to join the student Communist Party the very next day. She gave away all her clothes to the cyclone victims and adopted white saris, a symbol of sacrifice and political commitment. Rehana disliked seeing her daughter in white saris, but Maya remained unaware. She eagerly absorbed all the ideology shared by the party elders and began to speak passionately about uprising and revolution, as though she had uncovered a forgotten language.

Sohail’s political stance was different. He had the potential to become a prominent student leader, but he chose not to join any particular movement. He stated that he could not be influenced by any one faction. The distinctions between Communist factions meant little to him — whether they sided with Peking or Moscow, supported Mao or rejected him, or identified as Marxist–Leninist, Stalinist, or Bolshevist. Despite his neutrality, Sohail remained widely admired. He formed friendships across ideological lines and offended no one. He was popular among mullahs, rebels, artists, scientists, and students from various faculties. Girls, in particular, were drawn to him.

Rehana believed that her son’s popularity was not only due to his appearance but also his voice and demeanor. He spoke in a soft baritone and always stood with his hands behind his back, looking directly at whoever he was addressing. This posture made his presence both respectful and captivating. Women often followed him from Curzon Hall to Madhu’s Canteen, where he met his friends under the banyan tree, a historic gathering place for Dhaka’s student movements.

Despite all this, Sohail had deeply loved Silvi. His affection for her had persisted over many years. He had loved her when they watched Cleopatra the summer after his father died and again when they watched Roman Holiday. He had loved her since their school days, when she wore a blue and slate uniform, and even more when she started to mature physically. He had loved her when they exchanged poetry and romantic letters. At university, they rode home together in rickshaws, their knees knocking over potholes. He loved her when she began reading the Koran and when she agreed to an arranged marriage. He continued to love her even after she shut her bedroom window against him and refused to answer when he gently tapped on the shutters with the rubber end of his pencil.

Rehana acknowledged the likely truth in Mrs Chowdhury’s remark. Sohail was still young and inexperienced. He would eventually recover from his first heartbreak, as men often do. Still, Rehana felt that the party had not been a success. It had been meant to celebrate the children’s return on the anniversary of the day she had brought them back ten years ago.

Lying in the dark, Rehana began to recall that day, as though watching an old film reel. Though rusty and clicking, the images remained clear and emotionally powerful. This remembrance formed the final part of her nightly ritual — an effort to revisit the past and seek understanding.

Rehana makes the painful decision to sell Iqbal’s beloved Vauxhall. Mrs Akram proposed that Rehana sell the car to her husband, stating that he admired it and that she could persuade him to offer one thousand rupees. Initially, Rehana refused. However, after paying her lawyer, she was left with only two hundred and fifty rupees and decided to accept the offer. She instructed Mrs Akram to collect the car the following morning while she would be at the bazaar, as she did not want to witness its departure. Upon returning that afternoon, Rehana found the car gone, replaced by an oily stain and bare patches in the driveway.

The sale of the Vauxhall yielded one thousand rupees, which was still insufficient to meet Rehana’s financial needs. She needed money to bring her children back, raise them, and provide for their necessities. As a result, she pawned the remainder of her jewellery, including a sun-shaped locket with matching earrings, a ruby ring, and several gold chains. This brought her total to two thousand six hundred and fifty-two rupees, which remained inadequate.

Next, Rehana sold a carved teak mirror frame from her dressing table. This mirror had sentimental value, having been a gift from her father during her wedding, accompanied by a note expressing regret that it was all he could save. The mirror reminded her of her father’s decline, his loneliness in their Calcutta mansion, and the loss of family possessions to creditors.

Mrs Chowdhury suggested a new plan, prompting Rehana to hire an architect in May, two months after her court battle. She instructed the architect to build the largest and grandest house possible. Construction began in July, with workers laying cement and girders under the intense midsummer heat. However, by August, Rehana’s funds were exhausted.

Rehana approached various banks for a loan, including Habib Bank, United Bank, and National Bank. Without a guarantor, she was told she could mortgage her land, but she refused. Eventually, a man agreed to help. He brought her to his office, where he touched her arm suggestively. Rehana almost agreed until she noticed his unpleasant breath and yellowed teeth, which made her recoil. She fled the room, still holding her green fountain pen.

Months passed. Moss grew on the unfinished foundations. During the monsoon, the site turned into a flooded, stagnant pond. Rehana observed tadpoles and garden snakes in the waterlogged pit, symbolising the decay of her stalled dreams.

Eventually, Rehana found the money she needed, although how she acquired it remained a secret. She chose to keep the memory private, carrying the emotional burden alone as a testament to the lengths she went to for her children.

After that, the construction progressed rapidly. By the end of the year, the walls were up. Two months later, the plaster was complete. By March, the spring heat dried the blue-grey whitewash. Rehana watched as her carpenter, Abdul, carved the name “Shona” into a piece of polished mahogany. When asked if it was her mother’s name, she replied that it was simply the name of the house — a symbol of what she had lost and wished never to lose again.

Rehana advertised the house in the Pakistan Observer. The ad described a new four-bedroom house in Dhanmondi with a large lawn, requiring six months’ rent in advance. Mr and Mrs Sengupta responded to the ad. Mr Sengupta, a tea plantation owner from Sylhet, was often away and wanted a place where neighbours could keep his wife company. Rehana agreed and stated her requirement for six months’ rent in advance.

Mrs Sengupta, named Supriya, told Rehana she was writing a novel and admired the writer Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain. She asked if Rehana had read Sultana’s Dream, which Rehana had not. Regardless, Rehana agreed to the rental. Mr Sengupta handed over the rent in a toffee-coloured envelope, and Rehana gave him the keys.

The next day, Rehana visited the judge, received the court order, packed her belongings, and took a PIA flight to retrieve her children.

Rehana vividly remembered the reunion. She found her children playing hula hoops on the lawn. Their appearances had changed — they were darker and taller. The sight overwhelmed her with disbelief. Even years later, she still sometimes relived the moment when she reclaimed her role as their mother.

She finished recounting the story to herself and allowed the tears on her cheeks to dry.

The narrative then transitions to a public cricket match. Bangladesh was leading, and when Azmat Rana scored a half-century, the crowd erupted in celebration. People cheered, banged drums, and shouted “Joy Bangla!” repeatedly. As he reached his second half-century, the stadium was in such an uproar that the announcer’s voice was drowned out. Families filled the stadium, enjoying picnics and watching the match in the blazing sun.

Rehana had brought chicken sandwiches and passed them to her son Sohail, who was sitting nearby with his friends Aref and Joy. Sohail thanked her, gave her a slight smile, and shared the sandwiches.

Rehana sat with Maya and Mrs Sengupta. Mrs Sengupta asked if a wedding date had been set. Rehana replied that it had not. Mrs Sengupta commented on Maya’s youth and questioned the rush. Instead of responding directly, Rehana touched her arm and suggested they get drinks.

Sohail called the drinks vendor and asked for lemonade and orange. When he reached for money, Mrs Sengupta insisted on paying. Sohail accepted and sat down.

As Azmat Rana stands at the crease, Rehana tries to get a clear view of him. She climbs onto a bench, shielding her eyes from the bright afternoon sun. A sense of euphoria rises within her, and she begins to giggle openly, reflecting that this might be the happiest day of her life. She momentarily dismisses recent worries, particularly concerning her daughter Silvi, and focuses instead on her son Sohail, who is enjoying the game with his friends.

Maya notices her mother descending from the bench and is surprised. Rehana playfully comments on how handsome Azmat Rana is and offers Maya some lemonade. Meanwhile, Nigel Gifford is preparing to bowl, and Sohail is engaged in a political discussion with his friends. They debate systemic issues such as the military-industrial complex and the legitimacy of Mujib’s electoral victory. Sohail insists that real change would only occur through economic reforms, while Aref emphasizes the urgency of forming the national assembly and installing Mujib as Prime Minister.

As Nigel is about to release the ball, a subtle yet palpable shift overtakes the crowd. The atmosphere turns tense. The roaring in the stadium no longer seems directed at the game. Confusion arises among the players and spectators alike. Objects like bricks and sticks are hurled onto the field, and torn newspaper begins floating down from above. Sohail hears from a nearby group that something is being announced on the radio. Realizing the situation is deteriorating, Rehana begins packing up their things, but Sohail urges her to leave them and evacuate.

A chaotic scene unfolds as people surge towards the exits. Rehana tries to maintain contact with Maya and locate Mrs Sengupta. She clutches Maya’s arm tightly while navigating through the disoriented crowd. The players abandon the game and drift toward the edge of the field. Azmat Rana looks toward Ramna Racecourse, a site of previous celebration. The announcer’s voice is drowned out by the rising panic, and his call for calm is ignored.

Outside the stadium, Sohail gathers their group and leads them to the car. He takes the wheel of Mrs Sengupta’s Skoda Octavia. Joy and Aref join him in the front, while Rehana, Maya, and Mrs Sengupta sit in the back. Rehana tells Maya to keep the window up for safety. As they drive through the familiar streets, the usual sight of public gatherings now seems ominous. Rehana senses impending calamity and tries to make eye contact with Sohail, who remains focused on driving.

The car enters the university compound and passes by significant landmarks such as Curzon Hall and Rokeya Hall. In front of the Teacher–Student Centre, they see a growing procession of people wearing black armbands and chanting political slogans like “Joy Bangla” and “Joy Sheikh Mujib.” Maya enthusiastically joins in the chants from inside the car.

Sohail attempts to reverse the car to avoid the oncoming crowd but finds it blocked. The crowd surrounds the vehicle, banging on it and shouting slogans like “Death to Pakistan” and “Death to dictatorship.” The demonstrators press their faces and fists against the car’s windows. Recognizing Sohail, a boy named Jhinu knocks and peers inside. Sohail lowers the window slightly, and the two exchange information.

Jhinu informs them that the assembly has been indefinitely postponed. Bhutto has allegedly convinced President Yahya that a Bengali cannot lead Pakistan. Maya and the others react with disbelief and anger. As the conversation unfolds, Rehana realizes that this brief exchange is shaping a new course of action for the young men, particularly her son. She feels the ground shifting beneath her authority.

Rehana urges Sohail to drive away as the crowd begins to thin. Sohail confers with his friends and eventually agrees. However, just as they are about to leave, Mrs Sengupta offers to take over driving, suggesting the boys should rejoin their peers. Rehana is apprehensive but eventually relents after some persuasion. She fears for their safety but does not resist strongly.

Sohail parks the car near Rokeya Hall and leaves the engine running. He reassures Rehana that he will return soon after finding out more about the situation. Rehana, trying to suppress her rising panic, bids him farewell. She knows she might not be able to stop him from joining the unfolding political movement.

Mrs. Sengupta waits in front of the car, ready to drive as she tries to comfort Rehana by telling her not to worry. However, a thin boy in a lungi rushes past, causing Mrs. Sengupta’s sari to slip from her shoulder. As she bends to fix it, she trips, hitting her head on the wheel before she can break her fall. Rehana immediately rushes to her, asking if she is hurt. Mrs. Sengupta dismisses the incident as nothing serious, though she is slightly shaken. Rehana offers her a handkerchief to clean herself up, and Mrs. Sengupta notices she has lost her teep (a decorative dot on her forehead). She reassures Rehana, laughing nervously as she fixes her appearance.

The scene shifts to Maya, Rehana’s daughter, who is watching a procession from the car. Upon arriving at their bungalow, they are greeted by Sharmeen, Maya’s best friend and a politically active art student known for her political posters. Sharmeen has a large roll of paper and asks for help with it. Maya explains they had been stuck in traffic after the cricket match, and Sharmeen quickly joins them at the bungalow. Rehana, who has a welcoming attitude toward Sharmeen, offers her a place to stay, as she often does. The bond between Maya and Sharmeen is further highlighted, and the narrative reflects on their childhood friendship, marked by shared experiences of loss and a mutual need for each other’s company.

In the drawing room, Maya and Sharmeen examine one of Sharmeen’s posters. They debate whether it needs more color or if the blank space on the canvas signifies the future. Rehana, feeling a bit weary, retreats to her room, reflecting on the earlier incident with Mrs. Sengupta and the actions of Sohail, her son, who is often the voice of reason. Rehana wonders about the political movements her children are involved in, feeling both detached and somewhat uneasy about their intense involvement.

Hours later, Rehana reemerges from her room to find Sohail and his friends gathered in the drawing room. Sohail invites her to a meeting led by Mujib, the leader of the nationalist movement, who is calling for a declaration of independence. Despite her uncertainty and hesitation, Rehana decides not to attend, feeling disconnected from the revolutionary fervor her children embrace. She reflects on her own inability to fully participate in the political language of the movement and her sense of fading out of her children’s lives as they grow into adulthood and their activism.

After the meal, Sohail presents Rehana with a gift: a flag of East Pakistan, sewn in the colors of green and red with a map of East Pakistan at its center. The gesture symbolizes their growing nationalist pride. Maya, excited by the flag, drapes it around herself and runs off to find a pole to display it. The mood shifts to one of fervent nationalism, and the household becomes filled with energy and passion for the cause.

Following the cricket match, the days become filled with political unrest. Sohail and Maya, heavily involved in student protests and strikes, return home late every night, discussing the sense of change in the air. However, life in Dhanmondi, where Rehana lives, remains relatively calm, with the exception of occasional visits from Mrs. Chowdhury, who brings gifts for her daughter’s upcoming wedding. One day, Mrs. Chowdhury arrives with velvet boxes containing jewelry, signifying the continuing preparations for her daughter’s wedding.

Despite her initial reluctance, Rehana attends a political rally on March 7th at the racecourse. The grounds are packed with people, and Rehana can see the small figure of Sheikh Mujib in the distance. As he delivers his speech, calling for every home to become a fortress, Rehana feels the weight of the moment. The crowd’s excitement is palpable, and Rehana, swept up in the fervor, finds herself shouting the slogan “Joy Bangla” along with them. Maya looks at her with a proud, encouraging smile, and Rehana is momentarily caught up in the revolutionary excitement, feeling a sense of youthful possibility.

Rehana reflects on the power of the moment and her place within it. As she participates in the rally, she experiences a brief but intense connection to the revolutionary spirit her children embody, even as she remains unsure of her own role in the movement.

She reflects on her physical transformation at the age of thirty-eight. Her body has become more reflective of her life experiences, particularly those tied to raising her children. Rehana’s appearance, once youthful and unmarked by the passage of time, now carries the visible signs of age and motherhood. She has gained weight, which brings with it a sense of comfort and an awareness of her body’s changed shape. This includes a new fullness in her belly, a slight heaviness in her limbs, and a noticeable thickening in her waist and ankles. These changes are accompanied by more subtle signs of aging, such as a deepened line between her nose and chin and a faint shadow above her lip. Rehana sees these physical changes as markers of a woman who has fought through the challenges of raising her children, a process that has left its marks on her body.

In a quiet moment of emotional solidarity, Rehana’s daughter, Maya, leans over and takes her mother’s hand. This act is not just a gesture of comfort, but a sign of unity. Maya holds her hand in a way that reassures Rehana of her strength and connection to her daughter. For a brief moment, Rehana feels a renewed sense of hope. She believes that the political turmoil surrounding Sheikh Mujib’s leadership and the uncertain future of the country will eventually resolve. Rehana envisions a future where Sheikh Mujib becomes Prime Minister, the country stabilizes, and their lives can return to a semblance of normalcy. She envisions a future where she and her children can continue their lives, free from the chaos and uncertainty of the present.

Rehana feels a sense of peace, believing that the political and personal struggles they are facing will eventually pass, and they will resume their ordinary lives. This moment of certainty offers her a fleeting glimpse of hope for the future, grounding her in the belief that everything will return to a place of normalcy.

The chapter opens with a sense of confusion and disconnection in the city as military planes land at the airport. The people, including the characters, struggle to understand what is happening around them, unable to grasp the seriousness of the situation. They later reflect that they should have sensed the impending violence, but they did not.

On the evening of March 25th, Mrs. Chowdhury invites her neighbors to dinner in honor of Lieutenant Sabeer. Despite rumors of a military attack circulating throughout the city, she insists on the gathering, even suggesting that Silvi and Sabeer have a small ceremony to mark their engagement. Rehana, feeling compelled to attend, agrees, and Sohail joins as well, likely to test himself amid the tensions.

Maya, however, is in a darker mood, frustrated by the quietude of the neighborhood as she feels the revolution is imminent. She expresses her desire to be out on the streets, singing revolutionary songs and distributing leaflets.

The group sits down for dinner, and despite the undercurrent of tension in the city, they continue with the evening. Silvi is dressed in a turquoise salwaar-kameez, and Sabeer wears his military uniform. The party, though subdued, goes on, and everyone raises their glasses in a toast, with Rehana sitting next to Sohail. After the toast, Mrs. Chowdhury carves the lamb, and they eat, oblivious to the events unfolding outside. The sound of the outside world, including the fruit dropping from guava trees, does not reach them.

Suddenly, at 10 p.m., the distant sound of gunfire breaks the calm. Tanks begin to fire, and chaos erupts in the city. Mrs. Chowdhury is alarmed, and as panic sets in, Sabeer instructs everyone to stay calm and remain where they are. Mrs. Sengupta insists on leaving with her child, Mithun, but Sabeer and Sohail rush to the roof to investigate the source of the commotion. Mrs. Chowdhury is distraught, clutching her chest in fear, and the others try to understand what is happening, but the gunfire is overwhelming.

As the shelling continues, Rehana is filled with a deep desire to protect her children, but Maya remains transfixed by the window, and Sohail and Sabeer are still on the roof. Maya tries to use the telephone and radio, but both fail to work, leaving them isolated. Meanwhile, from the roof, Sohail and Sabeer witness the horrors of the city, with the fires and destruction in the distance.

Sohail and Sabeer discuss their next steps. Sohail acknowledges the threat of desertion, but Sabeer expresses his uncertainty, revealing the internal conflict he feels as a soldier in the Pakistan Army. Eventually, the two return to the dinner gathering, where the atmosphere is tense and uncertain. Mrs. Chowdhury is still sitting, dazed, while Mrs. Sengupta tends to her child. Maya continues to try to find a radio signal, while the others wait, unable to act, filled with a sense of helplessness.

Mrs. Chowdhury rises from her chair, as though she has just had a sudden realization. She tells Sabeer, in a tense tone, that trouble is coming, and she insists that he must protect her daughter, Silvi. Mrs. Chowdhury worries about the possibility of harm from people or the army. She emphasizes the importance of making sure that Silvi is safe, asking how Sabeer can be certain she will be protected. Sabeer reassures her, but Mrs. Chowdhury remains concerned, suggesting that the only way to ensure Silvi’s safety is for Sabeer to marry her that very night.

Sabeer, confused and reluctant, asks if she is serious. Mrs. Chowdhury explains that she has experienced situations like this before, and the best thing to do is to ensure that all unmarried girls are protected. She questions whether the gate will keep danger out and urges Sabeer to marry Silvi immediately. She further stresses the urgency, claiming that there may be no other time, especially if the Lieutenant does not return soon. She insists that Rehana help by selecting verses from the Holy Book for the ceremony.

As Mrs. Chowdhury leaves to prepare Silvi, Maya mutters under her breath, criticizing Silvi for going along with the idea. Rehana, meanwhile, reaches for Silvi’s Holy Book and asks Sohail to help her retrieve it from the shelf. Sohail expresses his feelings about not loving Silvi anymore, mentioning that he stopped loving her once he learned about the soldier. Rehana remains silent, while Maya challenges Sohail’s stance on violence, calling Silvi weak for succumbing to the pressure. Sohail, however, defends Silvi’s autonomy, stating that women must have the right to make their own choices.

Rehana opens the Holy Book, and soon after, Silvi and Sabeer are seated together on a double sofa. Silvi, looking down at her lap, trembles, but just before Rehana can ask her if she is sure about the marriage, Silvi flashes a smile at her mother, which silences Rehana’s doubts. Silvi then asks Sohail to take a photograph, offering him the camera he had lent her earlier. Sohail, somewhat reluctantly, agrees and takes the photograph, though Rehana wonders what he sees in Silvi’s expression.

The lights suddenly go out, and Rehana is forced to recite the marriage verses from memory. Silvi and Sabeer exchange rings, and Mrs. Chowdhury, eager for a sense of normalcy, insists on having a poem. Sohail, however, protests, but Mrs. Chowdhury presses him, and Rehana tries to redirect the request to Maya, suggesting she sing a ghazal. Maya, however, ignores them, keeping her back turned.

Silvi, under her veil, begins to tremble violently, prompting Mrs. Sengupta to comfort her, saying that she is no more unhappy than any other bride. Mrs. Chowdhury’s insistence on the poem continues, and Sohail eventually recites a verse, which speaks of devotion, heartache, and adoration. As the poem ends, the group remains in Mrs. Chowdhury’s drawing room, listening to the distant sound of machine-gun fire. The night drags on in a surreal silence, with no further movement or conversation between them, leaving the scene in a tense and dreamlike stillness.

At dawn, the sounds of gunfire gradually fade, and the sun begins to rise, casting a soft pink and orange hue across the sky. Dust settles over the trees and rooftops as the quiet of the early morning takes over. Rehana and her family return home to find Mrs. Chowdhury asleep in her chair, her hand resting under her chin. They open the front door to discover Juliet, the dog, pacing around a motionless Romeo. Juliet circles the dog and grunts quietly, but Romeo remains unmoving. Sohail examines Romeo and concludes that the dog must have died from a heart attack.

Back inside their bungalow, Rehana instructs the children to rest, but they all remain in the drawing room, not moving. Later in the afternoon, a truck stops in front of the house, and the silence of the street amplifies every sound. A megaphone crackles to life, demanding that the residents take down their flags, threatening arrest for anyone who does not comply, followed by an insult: “bastard traitors.” In response, Maya rushes to the roof to remove the flag, wrapping it around her shoulders after she finishes. Rehana watches as Juliet barks from Mrs. Chowdhury’s yard.

As they sit and wait for something to happen, Sohail paces around the house, while Maya falls asleep wrapped in the flag. Rehana surveys their food supplies and calculates how long they will last. She estimates three days of rice and chickens, but later revises her estimate to five days after measuring again. The truck returns, announcing the temporary lifting of the curfew from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. the following day, with the warning that anyone found outside after 6 p.m. will be shot on sight. Juliet continues to bark as the truck departs.

When the curfew is lifted, Sohail and Maya leave for the university, and Rehana watches from the window as Lieutenant Sabeer, accompanied by Silvi, says a brief goodbye. She wonders how long it has been since she last slept and considers whether she should feel tired. Before she can decide, Mrs. Sengupta bursts in, informing her of a group of refugees that have arrived. Rehana peeks over the boundary wall into Shona’s garden, where she sees a movement in the grass. Mrs. Sengupta reveals that the refugees, mostly families and a few stray individuals, had just appeared on the street, seeking shelter.

Rehana agrees to let them stay and heads over to Shona’s house with food. She prepares a meal using their limited supplies: spicy chicken curry, korma for the children, cabbage and potato bhaji, fried okra with onions, and a stew made from spinach and pumpkin. After bringing the food to Shona’s, Rehana observes the refugees sitting in silence, sifting through their meager belongings. She becomes restless, wanting to understand what led these people to her doorstep. She decides to go to the university to learn more.

Rehana takes a rickshaw to the university, despite the rickshaw-wallah’s caution against it. As they travel through the city, Rehana notices that everything seems strangely quiet and almost normal, though the New Market area is shut down and boarded up. When they reach the university, the air changes, thick with smoke, and the rickshaw-wallah ties a cloth around his head and suggests that Rehana do the same. They continue through the street, noticing debris and litter scattered across the ground. Rehana briefly spots a pair of unbroken spectacles and a red ribbon on the road but is unable to stop.

As they approach Curzon Hall, the street becomes increasingly filled with rubble, and the crowd grows larger. Rehana is horrified to see a red ribbon leading into a gutter, where a young girl’s body lies. She tries not to look but cannot help feeling the trauma of the sight. The rickshaw continues, and Rehana later reflects on the gruesome scene she witnessed, including piles of corpses, dead rickshaw-pullers, and the destruction of university dormitories.

When Sohail and Maya return, their faces are etched with ash and exhaustion. They slowly recount the events of the night. They reveal that Mujib, the political leader, had been arrested and flown to West Pakistan. The army had launched an attack on the university, destroying dormitories and The Madhu Canteen. Tanks had bulldozed the slums near the Phulbaria rail track and targeted Hindu neighborhoods, where they used jeeps to fire through doorways and homes, killing indiscriminately.

In the evening, Rehana and the children were listening to the radio when an announcement was made. The speaker, identified as Major Zia, proclaimed the independence of Bangladesh. He declared,

“I, Major Zia, provisional Commander-in-Chief of the Bangladesh Liberation Army, hereby proclaim, on behalf of our great national leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the independence of Bangladesh. I also declare we have already formed a sovereign, legal government under Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. I appeal to all nations to mobilize public opinion in their respective countries against the brutal genocide in Bangladesh.”

Upon hearing this, Rehana realized the gravity of the situation: a war had arrived and had already begun. Whatever was going to happen had already been set in motion, and now she and the children would have to live in the shadow of the conflict. In this moment, Rehana wrapped her arms around herself and squeezed tight, hoping to summon the strength she once had. This act of self-comfort signified her attempt to prepare for the emotional and physical toll the war would impose on her and her family.

The chapter details the shifting dynamics and tensions in Dhaka as the city adjusts to military occupation during the Bangladesh Liberation War. The city gradually settles into an eerie routine under military rule. Soldiers patrol the streets, their grim faces and stiff uniforms marking the new normal. Tanks occupy the roads, and checkpoints are manned by soldiers who aggressively question drivers. This new order replaces the lively public demonstrations, resulting in a haunting silence, broken only by the curfew siren. The city feels ghostly, with the sounds of nature and the heat of the April sun marking the passage of time.

Rumors spread in this quiet environment. Some claim that the army has buried bodies in a mass grave or that prisoners are tortured in a warehouse on the outskirts of town. The deaths of animals in the Mirpur Zoo, including a Bengal tiger, are attributed to their fright. The news, however, is tightly controlled, with the newspapers proclaiming, “Yahya saves Pakistan,” while the city remains a shell of its former self, its people hiding their knowledge and fears.

As the city empties, many who were never truly residents – such as the butchers, tailors, and rickshaw-pullers – silently flee, leaving with their families and bundles. Rehana, reflecting on the situation, counts her blessings. Her children are safe, as are Mrs. Chowdhury and Silvi, although the latter’s situation becomes more complicated as rumors spread of those who have not survived.

Mrs. Akram, who had spent the night with her hands over her ears, is later revealed to have been in hysterics, fearing the end of the world. She had to be restrained by her husband, though she recalls none of it. She visits Rehana two days later, hiding the marks on her wrists with wide bangles, but she is alive. Romeo, however, is dead, and Mrs. Chowdhury has buried him under the tallest coconut tree in her garden.

Rehana reflects on Mrs. Rahman’s narrow escape from death. Mrs. Rahman had been invited to dinner with an old friend whose husband owned a tailoring shop in the old town. At the last minute, she had decided to decline the invitation due to her dread of the choked roads and the memories of the last visit. This decision saved her life when soldiers passed through the area and opened fire on the house. The husband was killed while his wife escaped with a minor injury.

The children, Sohail and Maya, manage to account for their friends. Joy and Aref, anticipating an attack, had barricaded Nilkhet Road and set fire to bottles, only to flee when the tanks crushed their barricades. They managed to escape to Curzon Hall, where the bullets narrowly missed them. However, Sharmeen is still missing. Maya, at first, feels left out of the action and is eager to hear a dramatic story from Sharmeen, but after several days without news, concern starts to grow.

On the fourth day, the Senguptas decide to leave. Rehana finds them preparing to leave, their belongings scattered in the drawing room. Mrs. Sengupta is visibly nervous, and Mr. Sengupta explains that it is unsafe for Hindus to remain in Dhaka. Despite Rehana’s concerns about reports of violence in the villages, Mr. Sengupta dismisses these as rumors and insists they are simply going to their village in Pabna. He assures her that there is no real danger. He becomes defensive when Rehana presses him about the trustworthiness of their village people, sensing her underlying concerns about the situation.

The Senguptas’ departure highlights the growing tension and the fracturing of the social fabric as people are forced to make choices based on their ethnicity and the escalating violence around them. Rehana’s thoughts are drawn to her own past, recalling a time when she had the luxury of retreating from difficult decisions. Now, however, the urgency of the present moment requires her to confront the reality of the situation.

Mrs. Sengupta, visibly concerned, apologizes for leaving Rehana alone and offers her money to help. Though Rehana protests, she reluctantly accepts the money, realizing that she will be without financial support until the Senguptas return. The couple’s attempt to leave in good spirits, despite the tension of the situation, lightens the mood. Mrs. Sengupta waves around the room, apologizing for the mess. Rehana reassures her, saying she and Maya will handle things. As they say their goodbyes, Rehana feels a sting of emotion, as she embraces Mrs. Sengupta and wishes her well.

By mid-April, the situation in Dhaka worsens. The military’s brutal campaign is spreading across the country, leaving destruction in its wake. Villages are burned, and reports of young boys joining the resistance are circulating. The city becomes increasingly dangerous as the army advances.

One day, Joy and Aref arrive at Rehana’s bungalow with a truck filled with crates. Rehana, surprised, asks them about the crates, and they explain that they need her help to store some items. Sohail, having emerged from his room, is similarly curious. The crates contain medicine and supplies, which Joy and Aref explain were taken from PG Hospital. Rehana, not wanting to press further, decides not to ask about how they obtained these supplies. She agrees to store everything, and the boys seem pleased that she understands.

The following day, the boys return with more supplies: powdered milk, rice, dal, cotton wool, and other essentials. Rehana, now with little space left in her house, finds herself walking around piles of stored goods. Her living situation grows increasingly cramped, with dining chairs stacked on tables and medicines taking up all available space. Despite the chaos, Maya finds comfort in the clutter, softly interacting with the supplies.

Amidst the increasing violence and fear, Rehana’s concern for Sharmeen, a girl who has gone missing, lingers. Maya, however, remains silent on the subject, and Rehana feels unable to reach her. Rehana asks about Sharmeen’s mother, who is in Mymensingh, and learns that Sharmeen has not been there. Rehana reflects on Sharmeen’s complicated life, including the fact that Sharmeen’s mother had remarried, and Sharmeen lived in a dormitory. She wonders if she could have been more compassionate toward Sharmeen and regrets not having a warmer relationship with the girl.

Rehana struggles with her relationship with Maya, who has become increasingly distant. Maya’s grief, shaped by the political atmosphere, has hardened her, and Rehana senses that Maya has changed physically, no longer looking young or pretty. Her daughter now wears widow’s white, a sign of her radical transformation. Rehana wonders whether she could have loved Maya better, as the child seems to be consumed by the political turmoil surrounding them.

Despite this, Maya still retains traces of her gentler self. Rehana notices that Maya cares for her long, thick braid and sings songs that soften her features. Although Maya’s politics have shaped much of her behavior, the tenderness in her singing voice reveals a deeper, more innocent side of her, connecting her to the traditional songs her mother taught her. These moments of tenderness provide a fleeting sense of connection between mother and daughter amidst the political and emotional turmoil surrounding them.

Rehana plays the harmonium, her hands delicate and focused on the task at hand. Though she is a devout non-believer, the act of singing feels like a spiritual submission to something greater. This sets the emotional tone for the chapter, where Rehana is deeply affected by her son’s impending departure and the larger political events unfolding.

The narrative then shifts to a visit from Sohail’s friends, Joy, Aref, and a Hindu boy named Partho. They arrive without the truck they had promised, appearing disheveled and on edge. They bring with them a black bag, which causes Rehana to be wary. Sohail is absent, and Joy calls out to him, but Sohail refuses to come. When Rehana steps out to speak with the group, she notes their rough appearance and the tension in the air. Despite her hesitation, she considers inviting them in, but they refuse, staying outside. Their conversation revolves around Sohail, and Aref asks about his well-being, suggesting the possibility of him coming to the window. Rehana tries to downplay the situation, telling them that Sohail is upset and not willing to meet them. The conversation leaves her confused and frustrated about Sohail’s sudden distance from his friends.

Later, at Shona’s house, Rehana and Maya are packing up the last of Mrs. Sengupta’s belongings when Sohail arrives, looking troubled. The two women engage in a conversation about the political situation, with Sohail expressing his concerns about international news coverage and the potential for foreign intervention. Maya presses him about his involvement with Aref, Joy, and Partho, suspecting they are involved in something dangerous. Sohail avoids directly answering her questions, but his nervousness is evident.

The tension escalates when Sohail finally reveals his plans to Rehana the next day. He informs her that he is going to join the resistance, as Bengali regiments have mutinied and there is a call for volunteers. Sohail’s decision is a shock to Rehana, who struggles to understand why her son, a pacifist, would make such a choice. She pleads with him, expressing her fear for his safety and urging him not to go. Sohail, however, insists that he has no choice, stating that it is not war but genocide, and he cannot stand by while others fight.

Rehana’s emotional turmoil is palpable as she tries to reason with him, reminding him that he always has a choice. She holds onto the hope that somehow, Sohail will change his mind. He reassures her with a promise not to leave without telling her, but she is filled with dread at the thought of him leaving in the middle of the night without her knowing.

The next day, Rehana and Sohail travel to the graveyard, where Rehana silently reflects on her thoughts and emotions. She struggles with the idea that Sohail is making the same decision that many young men in Dhaka are making – joining the fight, leaving their families behind. As they arrive at the grave of her late husband, Iqbal, Rehana silently appeals to him, wishing that he could intervene and prevent Sohail from going. She reflects on her own inability to stop him, even as she begs, “Don’t go.” Her emotional plea is a moment of pure desperation, and she hopes that somehow Sohail might find another way to help.

Sohail and Rehana share a silent, poignant moment, as he struggles with his decision to go, his internal battle evident. Rehana feels a sudden exhaustion as she hopes Sohail will change his mind, but he is determined to leave. The weight of his departure is felt deeply by Rehana, as she reflects on how similar he is to her in his approach to decision-making. She wishes she could forbid him from leaving, but she knows she has no power in this situation.

Rehana watches Sohail pack his belongings, noticing the posters on his wall, including those of Mao Tse-Tung, Che Guevara, and Karl Marx. Sohail keeps the details of his departure from her, saying it is better she does not know how he plans to leave. Rehana insists on being there when he goes and asks him to tell his friends Aref and Joy to pick him up. Sohail finally agrees.

As she continues her preparations, Rehana’s thoughts are interrupted by Maya, who hands her a red-wrapped package, asking her to open it later. Rehana feels a deep longing for a brother to send off, someone to love without worry. She then visits Mrs. Chowdhury, hoping for comfort, but Mrs. Chowdhury seems disconnected from the realities of the war, continuing to argue for trivial things, like wanting samosas despite the war’s devastation. Rehana’s concerns about the severity of the situation are dismissed by Mrs. Chowdhury, who reassures her that things will return to normal soon.

Feeling ill, Rehana is offered ice water by Mrs. Chowdhury. Sohail quietly whispers to her that he will leave the next day. Later, Rehana inspects Sohail’s packed bag, feeling both satisfied and nostalgic. She prepares a large feast for his departure, as if sending him off with a full stomach will protect him. However, Maya appears distant, a stark contrast to Rehana’s intense focus on Sohail’s departure.

At dinner, the family eats in silence, with Sohail being the only one to enjoy the meal. Rehana becomes aware of her neglect of Maya, who seems to have grown quiet and withdrawn. After the meal, Sohail prepares to leave. Maya, despite her stoicism, finally speaks to Sohail, urging him to “get the bastards.” She seems broken as he hugs her and leaves. Rehana says her final goodbye, urging Sohail to go with God’s protection.

Once Sohail leaves, Rehana tries to address her feelings with Maya, but her daughter remains elusive. Maya spends her days at the university, leaving early and returning late, consumed by an energy Rehana cannot reach. The house feels empty, and Rehana occupies herself by focusing on practical matters, like supplies and listening to the radio, while the war’s violence intensifies around them.

Rehana is visited by Mrs. Akram and Mrs. Rahman, who express concern over her well-being. Mrs. Akram suggests leaving the city for safety, but Mrs. Rahman resists, believing it is not necessary to flee. The conversation shifts to the question of whether Rehana should leave for Pakistan, but Rehana dismisses the idea, focusing on her children’s future and the need to remain in Bangladesh. Mrs. Rahman, in her defiance, urges everyone to take a stand against the occupation. Rehana, though unsure of what action to take, silently contemplates her next steps.

A few days after the events surrounding Operation Searchlight, Rehana grows increasingly concerned about her daughter, Maya. She decides to confront her, as Maya’s secrecy about her daily activities at the university has begun to trouble Rehana. She borrows Mrs. Chowdhury’s car and instructs the driver to take her to the university campus, unsure of where exactly to find Maya. Rehana feels anxious, suspecting that her daughter might be involved in something dangerous. She wants to uncover the truth and put an end to it, even though she wonders if her fears are unfounded. Regardless, she feels it is better to be certain.

Rehana reflects on her only previous visit to the university, which had occurred when Sohail invited her to the campus to try the famous phuchkas at the canteen. Rehana had bet Sohail that the best phuchkas could be found at Horolika Snacks in Dhanmondi, a place she and her late husband, Iqbal, had visited countless times. Sohail, however, was eager to prove that things had changed, and he persuaded her to try the university’s phuchkas. Despite her skepticism, Rehana eventually agreed, and they bought phuchkas from both Horolika Snacks and the university canteen for comparison. In the end, she chose the university’s phuchkas, signaling that indeed, things had changed.

Now, the university campus, including the canteen, had been destroyed during the massacre on the night of the crackdown. As Rehana’s car enters the university gates, she immediately spots Maya. Maya is in the front row of a group of girls marching, her knees raised higher than the others, and shouting louder. Rehana observes that Maya holds a wooden stick, pretending it is a gun, but she is not timid. Rehana watches with growing concern as the girls continue their mock drill, wearing starched white saris, looking serious. Maya appears to be at the center of this activity, and Rehana’s worries deepen.

After a few moments, Rehana opens the car door and waves at Maya, but her daughter does not notice. However, a boy standing next to Maya sees Rehana and points her out. Maya, irritated, walks over to the car, frowning. She confronts Rehana, accusing her of spying on her. Rehana explains that she was simply worried and wanted to see where Maya was spending her time. Maya, however, reacts sharply, stating that she is trying to contribute to the cause, and she dismisses Rehana’s concern.

The tension escalates as Maya questions her mother’s actions since they returned from Lahore. Maya accuses Rehana of having no real attachment to Bangladesh, of trying to keep her and her brother confined at home, and of not allowing them to take part in the current events. Rehana responds that everything she has done is for her children’s safety, and she demands that Maya get into the car because curfew is approaching. Maya refuses, insisting that she will stay at the university, leading to a physical confrontation. Rehana pulls Maya towards the car, using unexpected strength, while Maya resists and tries to free herself. Rehana insists, saying, “Don’t make a scene,” as she forces her daughter into the car.

On the ride home, they do not speak to each other. Once back at their house, Maya lashes out at her mother, accusing her of failing to protect her brother, Sohail, and of trying to keep Maya under control. Maya’s words cut deeply, especially when she mentions that Rehana’s efforts to protect them have been futile. Rehana tries to steer the conversation elsewhere, expressing sympathy about Sharmeen, but Maya refuses to talk about her. In a burst of anger, Maya accuses Rehana of having no understanding of the pain she and Sohail are going through.

Maya’s anger grows, and she bitterly remarks that Rehana should have left them in Pakistan. In the heat of the argument, Rehana unintentionally strikes Maya across the face. Maya, stunned by the slap, touches her cheek and then looks almost relieved. She responds coldly, saying that Rehana should have left them in Pakistan. Rehana, feeling a mix of regret and anger, stands silent, her jaw trembling, but she does not apologize. Maya stops speaking, and their relationship grows increasingly strained.

With Sohail and the Senguptas absent, and Mrs. Chowdhury and Silvi confined to their house, Rehana begins to feel a sense of isolation. The atmosphere at home becomes heavy, and Maya continues to retreat into silence. Rehana feels disconnected from her daughter, only able to gauge her presence through the faint sounds from her room: the soft click of the ceiling fan, the rustle of bed covers, and the turning of pages. This silent tension persists for two weeks, as the oppressive heat of April drags on.

One day, Maya suddenly announces the need for blankets for the soldiers and the collection of old saris to sew them. Rehana, suddenly struck by an idea, heads to the old steel almirah she has not opened in years. She finds the key hidden behind the lowest shelf in the kitchen, where she keeps emergency supplies like rice and dal. Rehana reflects on how her life’s variable fortunes had taught her to always keep a small reserve of items like rice and ginger.

As she opens the almirah, the familiar sound of scraping metal and the smell of mothballs and silk hit her. Inside are the saris that her late husband, Iqbal, had given her over the years of their marriage. She had preserved them meticulously, arranging them in the order of their presentation, remembering each occasion they marked. The saris reflect Iqbal’s growing prosperity and affection for her, moving from simple cottons to exquisite silks, the last being a blue Benarsi silk given to her shortly before his death.

Rehana studies the saris, recalling the sensations they evoked, their complexity as garments that both concealed and revealed. Although she had not worn any of them for years, she is not sentimental about losing them but laments that she will never have the chance to wear them again. Rehana gathers the saris in her arms and presents them to Maya, suggesting they use them to make blankets for the freedom fighters.

Maya, surprised, responds that she had requested cotton saris and questions the practicality of using expensive silks, which would itch when sewn into blankets. Rehana insists that the silk will keep the soldiers warm, as it is soon to be winter, and sharp words slip from her, revealing an unspoken tension with her daughter. Maya’s reaction is one of quiet resistance; she pleads with her mother not to give the saris away, but Rehana dismisses her concern with a harsh comment about Maya’s preference for white clothes.

Rehana, upset, decides to act on her own. She calls Mrs. Rahman and Mrs. Akram to the bungalow and leads them up to the roof, where she has laid out a jute pati and cushions, along with the saris and her sewing box. The women are surprised by her new venture, and Mrs. Rahman jokes that Rehana is opening a tailoring shop. Rehana explains that, with the war ongoing, she feels the need to prove her involvement, even if it is just by making blankets for refugees. She feels a tear rise but quickly pushes it back, emphasizing her desire to do something to help.

When Mrs. Akram asks about Sohail, Rehana explains that she sent him to Karachi to protect him from the soldiers, as university boys are disappearing. The conversation turns to Rehana’s decision to use the saris for the blankets. Mrs. Rahman gently suggests using old cottons instead, but Rehana stubbornly insists on sacrificing the silk. She justifies her decision by stating that everyone must make sacrifices for the country.

Mrs. Akram expresses concern for Rehana’s relationship with Maya, sensing tension, and Rehana admits that she slapped her daughter during their argument. The two women encourage Rehana to have more patience with Maya, but she responds bitterly, feeling overwhelmed by her responsibilities. She acknowledges that her relationship with Maya has been strained but cannot bring herself to fully admit her faults. Instead, she turns to the women for help in sewing.

On the last day of April, Rehana watches the rain fall, imagining it washing over the suffering refugees fleeing the war. She visualizes the rain falling on her son, Sohail, and his friends, who are far away, trying to survive with youthful defiance and poetry, unaware of the violence surrounding them. The rain, she thinks, symbolizes the sadness of their situation, falling over the land and the people, trying in vain to wash away their grief.

In the month of May, Mrs. Rahman and Mrs. Akram have taken up sewing with great enthusiasm, much like their previous interest in playing cards. They meet every week at the bungalow, bringing along their sewing kits. Mrs. Rahman, determined to support the war effort, secures a constant supply of old saris from her acquaintances and relatives, though she notes that no one is willing to part with their best clothes. Mrs. Akram, who had previously been considered a little spoiled, surprises everyone by stitching the fastest and even suggests adding sackcloth between the saris to make them more durable. She names their group “Project Rooftop,” to which Mrs. Rahman teasingly responds that she had once said they were not good for anything beyond cards. Mrs. Akram denies this remark, claiming it was not something she would say.

Rehana, the narrator, reflects that it has been two months since the war began in March, and the landscape of war is now a familiar one. They are accustomed to seeing soldiers in green uniforms, returning home when the curfew siren sounds, walking past closed shops, and observing empty streets. The hospitals are locked, and the fruit vendors’ baskets remain half full. This new reality, while strange at first, has now become ordinary, and everyone has adjusted to it in their own way.

However, Rehana’s relationship with her daughter, Maya, is strained. Maya remains angry at Rehana, and although Rehana feels the urge to apologize for hitting her, she cannot bring herself to say the words. Every time Maya returns from the university, their silence intensifies, and their interactions are filled with tension. The only time they share something together is when they listen to the radio. They regularly tune in to BBC Bangla in the morning and Voice of America in the afternoon. However, their most anticipated broadcast is the Free Bangla Radio transmission at 4:30 PM, which they know is being broadcast from a secret location in the liberated zone. The broadcast often reports on the refugee crisis, with one million refugees flooding into West Bengal, and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi pledging her support to the freedom fighters in Bangladesh.

In the middle of the night, Sohail returns to Dhaka. Rehana, who had been asleep, senses his presence when he stands at the foot of her bed and calls out, “Ma.” She presses her cheek to his, feeling a mix of relief and loneliness. He smells of petrol and cigarettes, and his clothes are dirty and too big. As she examines him, she realizes that he has changed in ways that are foreign to her, as though others have shaped him during his time away. She recalls his past life with Parveen, and the old wound of their broken relationship resurfaces.

Sohail wakes Maya, and the two siblings share an enthusiastic reunion. Maya is eager to hear about his experiences, particularly about the battlefront. They sit down to a meal of egg curry, fried eggplant, and leftover dal. As Sohail eats, he begins to share his experiences in the freedom-fighter army. He recounts how they took a ferry full of refugees and heard terrible stories about the violence against Hindus. He mentions that the Sengupta family has not returned, and Rehana reassures him that they are fine, though they hardly see them anymore. Sohail then continues, describing how they eventually found a camp of Bengali regiments after a three-day search. The camp was initially temporary but has since grown into a small town with hospitals, barracks, and various military sectors.

Maya and Rehana have been listening to the radio reports about the situation, and Maya asks where Sohail sleeps. Sohail explains that they sleep in tents, which are uncomfortable, and jokes that he will need blankets and a proper plate when he returns. Rehana tries not to show her disappointment that Sohail is planning to return to the front lines, but she cannot help feeling it. She recalls his old love for Elvis Presley and wonders about the strange life he is now living.